Blog

My Interview in the Big Thrill Magazine

1/31/2021

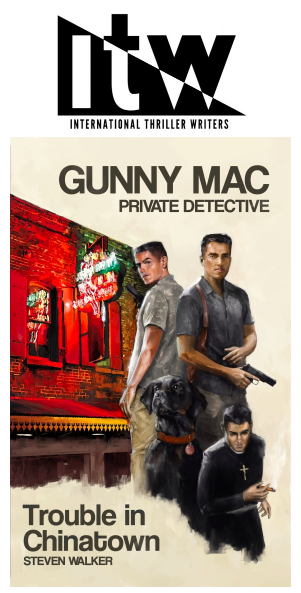

Gunny Mac Private Detective Trouble in Chinatown by Steven Walker

by Tim O’Mara, originally published on thebigthrill.org

It’s the onset of World War II. President Roosevelt is collecting and burning the currency in Hawaii in case the Japanese invade. Corrupt military officers, gangsters, and police officials are poised to steal as much of that money as they can. A badly wounded Marine Gunnery Sergeant and three other wounded veterans team up to stop them.

Got it? Good. That’s the plot of Steven Walker’s crime thriller, Gunny Mac, Private Detective—Trouble in Chinatown (Seadog Publishing, October 2020.)

This novel clearly took a lot of research. I asked Steven to talk a bit about that.

“I stumbled upon the fact about Roosevelt wanting to burn the money,” he began, “because he felt that the First Marine Division was going to be defeated on Guadalcanal which would leave Hawaii free to be invaded by the Japanese and our resources used against us. I downloaded the actual five-hundred-page official after-action report on what took place during this crucial time. I spent about eighty hours of research online and went through my personal military library. I knew a lot about this time period and noir private detective fiction.”

Steven’s father was a military man. How did that play into the writing process?

“My dad was a terrific storyteller and I grew up laughing all the time. He relayed to me many personal experiences in Hawaii like drinking as much beer as possible, eating French fries, and throwing up all over the street. He was eighteen years old. They trained in Maui and lived in tents to get ready for Iwo Jima. He told me much about the Marines in 1943 through 1947.

“My own years in the Marines shaped me and allowed me to write what I know. I can still feel the jungle heat and humidity, the smell of wet canvas, jungle rot, and, of course, all the good and bad characters, officers and enlisted. All my characters are men I knew, including Padre McCaffery, who drank bourbon like water, smoked cigars like they were free, was brave, and loved God.”

Not being a military man myself, I asked Steven what makes a good Gunnery Sergeant a good P.I.? I could feel his smile.

“Great question!” he said. “In the 1930s and ’40s, Marines who made it to this rank were harder than woodpecker lips. They had fought insurrections, guarded mail trains; the Marine Corps was their family. Like the gunnery sergeants of today, they were the backbone of the Corp: they led men, trained them, and disciplined them. They’re a cagey lot, prone to rebellious streaks, profane, yet profess a love of people. They have a code of honor and won’t break it. They will walk a mile out of their way to take care of bad guys and bend over backward to help a young Marine. They’re smart about the ways of the world (and often kept me out of trouble.) They will fight until they die, and live life to the fullest. They’re also the funniest people I’ve ever known. Good humor comes from men who are in a bad situation and make fun of it.”

Sounds like someone I’d want watching my six.

Trouble in Chinatown is filled with enough bad guys for two books. What makes a good antagonist and what does he or she bring out in our hero?

“First,” he explained, “I don’t like terrible, horrible villains. I feel they must have some good and not totally dark like today’s modern villains whereby in the third chapter they are cutting hearts out and mailing them to people. I stop reading. My villains are more like Casper Gutman in the Maltese Falcon: fat, sneaky, bad, but with a sense of humor and some good. Then there’s Johnny Friendly, the gangster in On the Water Front. Lee J. Cobb plays the bad guy who uses other people to bully and kill him. In the beginning, he is the successful gangster, but by the end, the beast within him—the wounded animal—becomes clearly visible, as he’s revealed to be as human and vulnerable as the poor people he exploited.

“Just as our hero is about to turn bad,” Steven continued, “and maybe lose his soul, he is saved by the villain’s cruelness. He has a choice to stay decent or turn bad. Because he has a code of honor, he stays on the right side of being human.”

While reading this novel, it became quite clear to me that Steven was not just a fan, but also a student of noir fiction. I asked the obvious: Who are his major influences?

“Brett Halliday, a pseudonym for Davis Dresser; I love his wisecracking funny detective, Michael Shayne. Mickey Spillane, who wrote about Mike Hammer. Earl Derr Biggers who introduces us to Charlie Chan, the Chinese detective in Honolulu. Samuel Dashiell Hammett—Sam Spade, Nick and Nora Charles, and the Continental Op. Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, whose FBI agent, Aloysius Xingu L. Pendergast, is one of my favorite detectives.

“And my dear father, of course, who introduced me to all these great writers and the films they inspired. Thanks, Dad.”

I knew that Steven is, like me, a huge baseball fan. I wanted his opinion on how a good novel is like a good baseball game.

“You and I are on the same wavelength,” he told me. “First of all, it is an American game and noir detective fiction is all-American. Both have deep roots in our culture. Baseball starts slow, sometimes like a novel, and the tension builds until you are eating your fingers to the quick. Your heart is beating a mile a minute and you are standing, waiting for your hero to hit it out of the park. I believe it’s the most dramatic sport in our culture. The same with a novel: conflict and tension build until you must have a satisfying ending with your hero saving the day. When I hear a baseball game over the radio, my heartbeat goes down and a peacefulness comes over me. A good novel leaves me in that same pleasant state of euphoria.”

As for Steven’s personal journey as a writer…

“It took me five years to be a writer,” he said. “I fought it. I didn’t want to put in the work. I was working full time and just played around with my ideas. I didn’t know what I was doing until I found out about the concept and premise. (Thanks Larry Brooks!) When I understood those two ideas, I wrote my novel in nine months.

“(With Trouble in Chinatown) I had fifty-five rewrites and countless edits. I realized I had to stop tweaking it because a writer is never satisfied with what they have written. I have the sequel—Gunny Mac Private Detective Trouble in Cleveland—half complete. Once I had my characters, they wrote the book for me. Someone asked me how I felt about finishing and publishing my novel. Like I feel after finishing an infamous twenty-mile forced hike in the Marine Corps in a little more than three hours—tired, but thankful I didn’t fall out.”

Finally, I asked, “How about your dream panel at ThrillerFest?”

“Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Mickey Spillane, Dean Koontz, Stephen Hunter, Preston and Child, and Nelson Demille. The subject? What makes the quintessential American detective and how does he or she relate to your heroes?”

%20(18)_1664167537412.png?alt=media&token=fdbea484-b534-4c19-9234-c089ede5e7a3)